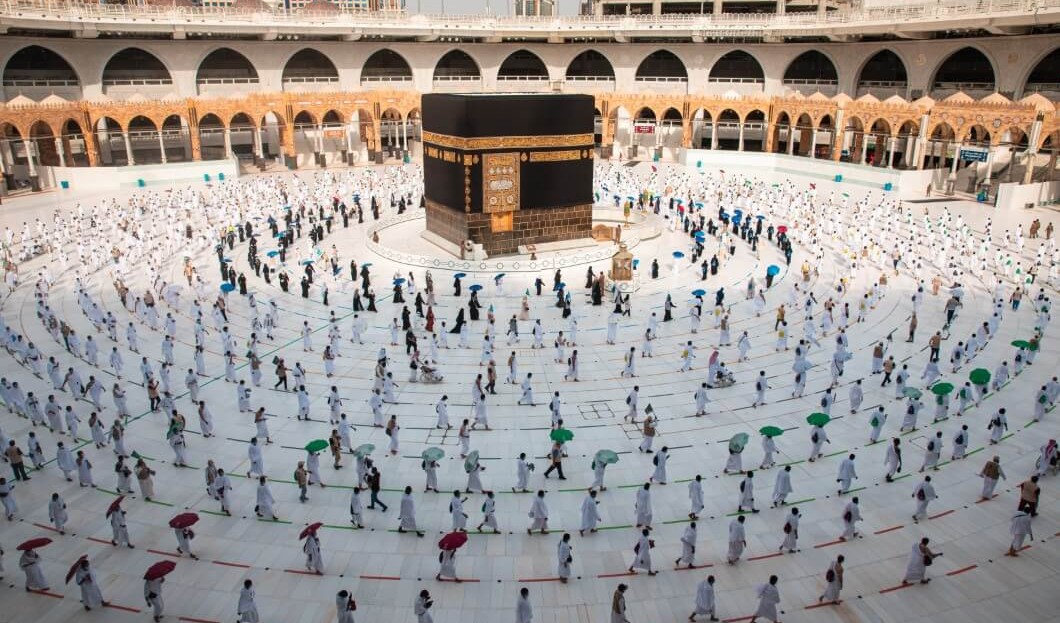

Hajj, the largest pilgrimage in the Muslim world, began in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. But this year, again due to the pandemic, only a few tens of thousands of pilgrims were allowed to participate. Some loss of income for the first Gulf economy and the possibility of religious tourism have been severely affected by the pandemic around the world.

For the second year in a row, the Saudi government has sharply reduced the number of Muslims participating in the Hajj, which was held from 17 to 22 July 2021: 60,000 pilgrims, all residents of Saudi Arabia, aged 18 to 65, do not suffer from chronic diseases and, first of all, properly vaccinated. This is far from the two and a half million pilgrims who flocked to the holy city of Mecca in 2019 from around the world.

The loss of income for the economy of Saudi Arabia is significant. Prior to the pandemic, the Hajj brought the kingdom an average of $ 10 billion to $ 15 billion a year in addition to the $ 4-5 billion spent by about eight million pilgrims during the omra, a small optional pilgrimage that could be made year-round. Lost contingencies from religious tourism are equivalent to 7% of Saudi Arabia’s GDP. This is the second largest contribution to the country’s economy after oil.

This is a disaster for Saudi finances, but not the only one. In other parts of the world, especially in Africa, tens of thousands of travel agencies specializing in religious tourism, immediately found themselves out of business.

The global crisis of religious tourism

This situation is not limited to Saudi Arabia. Most major religious gatherings were canceled, with the exception of Kumbha Mel, a large Hindu pilgrimage that gathered up to 9 million pilgrims on the banks of the Ganges in April last year and within weeks. But India still pays a high price: today, more than 411,000 deaths are due to the spread of the Delta variant, which currently accounts for most new infections worldwide.

For example, in Europe in areas such as Lourdes in France, Santiago de Compostela in Spain and Fatima in Portugal, activity fell by an average of 75% last year.

The sharp decline in the number of pilgrims in these main places of pilgrimage has seriously affected the entire local economy, starting with the hotel and restaurant business.

After the abolition of the great pilgrimage, Lourdes, the second largest hotel city in France after Paris, last year recorded occupancy of only 25% of its facilities. About 2,500 seasonal workers in these industries lost their jobs. The number of closed shops, especially souvenirs, is innumerable. This year, the scenario is likely to be repeated again, and pilgrims will be forced to watch the celebration on screens.

Unbelievers to help religious tourism

Perhaps salvation for some of these things could have come from unbelievers. The pandemic has profoundly changed people’s attitudes towards tourism. Restrictive measures imposed to curb the spread of the virus have put an end to travel abroad. Consecutive restrictions have created a desire for nature, for wide open spaces. And the need to find yourself, to find the meaning of your life – has never been so.

In this context, pilgrimage may well become a new trend in travel after Covid-19. This is the case with the roads in Santiago de Compostela, which take more and more travelers, not just pilgrims. According to a study published in the journal National Geographic, 40% of pedestrians walking this route in France, Spain and Portugal are now non-believers.

Throughout Europe, Ireland, Wales, Finland and Sweden, there is a similar fascination with this type of travel, consisting of outdoor walks and visits to religious sites. These new types of pilgrims remain, consume and participate in the economy of the territories they cross. In short, they are a breath of fresh air for religious tourism in crisis.